Before we can explore conservation within the farmed environment we need to reflect on what people need every day of their lives. The images below illustrate our basic daily requirements.

|

Introduction:

The global demand on our agricultural systems is enormous, we are facing an increasing population and simultaneously a reduced rate of yield increase in our cropping systems. Put succinctly we have to double our food production within the next 30 to 40 years to meet future demands. From 1966 to 2006 rice and wheat yields increased at a relatively constant rate of about 52 kg ha per year, equivalent to about an annual 3% increase. Since 2006 this annual yield increase in rice and wheat has decreased to about 1.3% per year. There are many constraints to food production and increased crop yields that are far beyond the scope of this web page, but a brief list of the main threats is as follows:

In many temperate countries crop production is dominated by industrial scale arable including the winter and spring sown cereals:

|

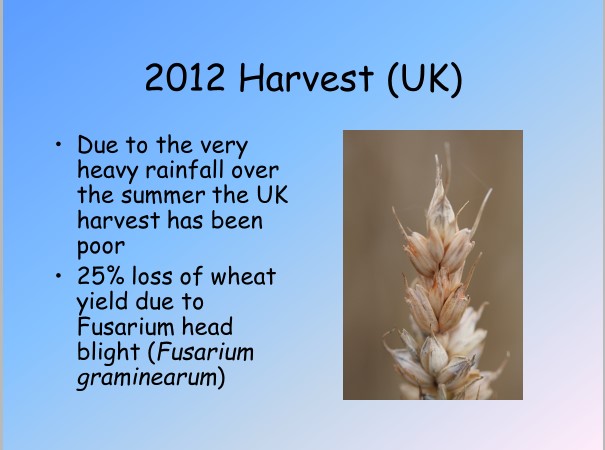

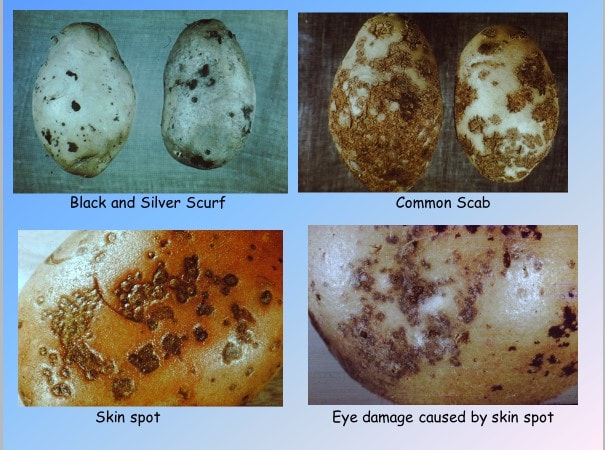

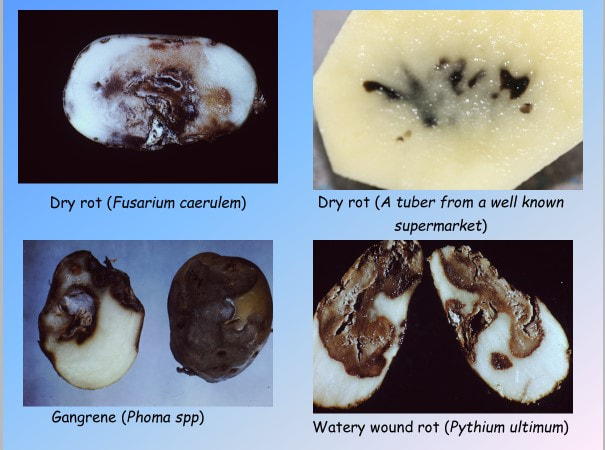

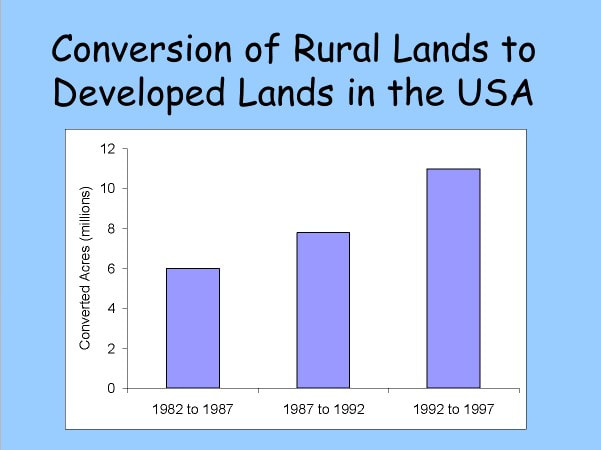

Pictures illustrate some main threats to food production systems. Starting top left; soil erosion from excessive winter rain 2019/2020, The impact of the excessive wet summer of 2012, Leaf blotch (Septoria spp) on wheat leaves, a major pathogen in the south west of Britain. Head blight of wheat, then crown rusts on oats. This picture illustrates the impact of foliage pathogens on a crop that has had no fungicide. Excessive weed infestation on a poorly established crop. Then two slides illustrating the impact of post harvest pathogens on potato and finally the urban sprawl, in this case Kuala Lumpur and the increase in land urbanisation in the USA.

|

|

There are alternatives to the industrial crop production system that afford opportunities for conserving habitats and species and environmental mitigation. Traditionally in Britain farming followed a mixed farm model:

In 1992 the EU adopted a multi-functional land use system, this is where farming and nature occurs in the same landscape. This differs from many other parts of the world where agriculture is carried out on a land sacrifice model, this is where large tracts of land are devoted to agriculture and the non productive landscape is designated as conservation, typically land at altitude. This system is extremely damaging to the environment in many ways but not least because of the many water courses that traverse sacrificed crop lands are vulnerable to agricultural run-off. |

Working left to right, from top left: Mixed farmed landscape in Cornwall, a mixed farm landscape in Hampshire, organic oats and grass fed beef, cattle are south Devon's.

|

|

The multi-functional land use system adopted by the EU states in the 1990's was a huge step in the right direction. This land use system accommodates both food production and nature conservation. It is not perfect but it does work.

The incorporation of nature conservation into the farmed landscape is a balance between the two competing sectors but with careful application and attention to both the ecological requirements of nature and the historic components of agriculture there have been some outstanding success stories in bringing nature back to the farm. Perhaps one of the best examples is the increase in Cirl bunting numbers in south Devon. In the 1980's and early 1990's the breeding population of this species was around 35 pairs, today (2020) the number of breeding pairs has increased to over 700 and some of these have been used to start new colonies in Cornwall. The importance of the historical component of agriculture can not be overstated in countries like the UK, because our farming systems are over 3000 years old and in that time nature has adapted to low yielding-low input systems:

|

|

Over the coming months i will share examples of on-farm CONSERVATION and the potential to rewild the farm landscape

Home

Explore Agriculture

Explore Conservation

Lowland Dipterocarp Forests of SE Asia

Explore Conservation of Dipterocarp Forests

Make a Difference

Private Courses

Explore Agriculture

Explore Conservation

Lowland Dipterocarp Forests of SE Asia

Explore Conservation of Dipterocarp Forests

Make a Difference

Private Courses